History

24 April 1980

A Battlefield Promise

At a remote airstrip known as DESERT ONE, a battlefield promise made to 17 American children – when 8 Special Operations Forces were tragically lost in a daring mission – OPERATION EAGLE CLAW – to rescue 52 American hostages in Iran.

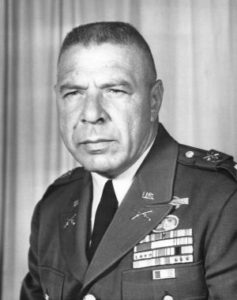

Special Operations Warrior Foundation (SOWF) began in 1980 as the Col. Arthur D. “Bull” Simons Scholarship Fund. The initial mission was to provide college educations for the seventeen children surviving the nine men killed or incapacitated at Desert One, the Iranian hostage rescue attempt. It was named in honor of the legendary Army Green Beret, Bull Simons, who repeatedly risked his life on rescue missions.

SOWF Expands eligibility to include ensuring the surviving children of all Special Operations Personnel Fallen in Combat, lost in the Line of Duty, spouses of active duty Special Operations personnel, and the children of all Medal of Honor Recipients.

Following creation of the United States Special Operations Command, and as casualties mounted from actions such as Operations “Urgent Fury” (Grenada), “Just Cause” (Panama), “Desert Storm” (Kuwait and Iraq) and “Restore Hope” (Somalia), the Bull Simons Fund gradually expanded its outreach program to include the children of all Special Operations Personnel fallen in combat.

In 1995, The Bull Simons Fund merged with the Families Action Liaison Group (established to support the families of the fifty-three Iranian hostages) and the Spectre (Air Force gunship) Association Scholarship Fund to form Special Operations Warrior Foundation (SOWF). In 1998, SOWF expanded the scholarship and financial aid counseling program to include the children of Special Operations Personnel fallen in training since the inception of the Foundation in 1980. This action immediately added 241 children who were now eligible for college funding.

Eligibility was expanded again in 2013 with the inclusion of surviving children of all Special Operations Personnel Line of Duty deaths. Most recently, program eligibility expanded in 2020 to include the children of all Medal of Honor Recipients.

“Special Operations Warrior Foundation was founded after my father Joel C. Mayo was killed during Operation Eagle Claw in 1980 in Tehran, Iran. I believe that it is important for organizations such as this to be able to honor the memory of the parent that has been taken from the student, and take away some of the concern for college education.”

SOWF Expands Eligibility to include SOF Operators severely injured in training and severely ill SOF Personnel

As SOWF matured, grew, and became better resourced, the programs and services it provided its constituents evolved as well. In 2006 SOWF expanded to include support of Special Operations Personnel wounded in combat, with a $2,000 stipend of immediate financial assistance. That stipend increased to up to $3000 per incident in 2012, and again increased to $5000 in 2016. In 2018, the immediate financial assistance program expanded to include those severely injured in training, and again expanded to include severely ill SOF personnel in 2020.

Under the guidance of the Board of Directors, education programs also evolved over time to more holistically support what became SOWF’s top priority in its Strategic Plan, developed in 2018: student success. In 2014, SOWF began funding unlimited tutoring for students in grades K-12.

Preschool grants of up to $5000 for students 3-5 years old began in 2017. These preschool grants expanded from students aged 3-5 to students aged 2-5 in 2019, and the grants increased to up to $8000 per student, per year in 2020. The SOWF staff developed and implemented its inaugural Educational Planning and Information Conference in 2015, to help high school students plan for and apply for attending the college of their choice. In 2019, SOWF formalized its support of students with learning disabilities, and designated a certified counselor to work with those families on their unique needs. Mentoring and Internship programs began in 2017, with SOWF hiring an additional counselor to develop those programs in 2019. In 2021, the foundation held its inaugural Strong Finish Optimization conference to assist college students and recent college graduates in the transition from college to career.

Operation Eagle Claw

On November 4, 1979, as many as 3,000 militant students stormed the United States Embassy in Tehrān, taking 63 Americans hostages. Three additional members of the United States diplomatic staff were seized at the Iranian Foreign Ministry. The incident took place two weeks after United States President Jimmy Carter had allowed the deposed Iranian ruler, Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi into the United States for cancer treatment. Iran’s new leader, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeni, called for the United States to return the shah, also demanding an end to Western influence in Iran. In the Shah’s absence, the Ayatollah seized leadership and built his dictatorship. By mid-November, 13 hostages (combined women and African Americans) had been freed. 52 hostages remained while negotiations for release began.

Meanwhile, American military commanders constructed a plan regarding a possible rescue mission, and training exercises were initiated to determine the readiness of troops and equipment. When the diplomatic process stalled, President Carter approved a military rescue operation on April 16, 1980. The ambitious plan, called: Operation Eagle Claw, utilized elements of all four branches of the United States Armed Forces (Army, Navy, Air Force and Marine Corps. The two-day operation called for helicopters and MC-130 aircraft to rendezvous on a salt flat (code-named Desert One) some 200 miles southeast of Tehrān. There the helicopters would refuel from the MC-130s and pick up combat troops. The helicopters would then transport troops to the mountain location from which the actual rescue mission would be launched the following night. Starting on April 19 forces were deployed throughout Oman and the Arabian Sea and on April 24, Operation Eagle Claw was coordinated and intended to be implemented.

The operation was almost compromised when a local passenger bus and then a tanker truck entered the area via a nearby road. To maintain security, the ground forces intercepted the bus, detaining more than 40 Iranians, and when the tanker did not stop, they fired an M72LAW anti-tank weapon into the vehicle.

Of the eight navy helicopters that left the USS Nimitz, two experienced mechanical failure and could not continue, and the entire group was hindered by a low-level dust storm that severely reduced visibility. The six remaining helicopters, piloted by Marines, landed at Desert One more than 90 minutes late. There, another helicopter was deemed unfit for service, and the mission, which could not be accomplished with only five helicopters, was stopped. On April 24, 1980, as the service members were exiting the area, a helicopter, due to an immense cloud of desert dust and unfortunate confusion, collided with a MC-130 and exploded, destroying both aircraft and killing five Air Force servicemen and three Marines. The remaining troops were quickly evacuated by plane, leaving behind those who perished along with several helicopters, pieces of equipment, weapons, and maps.

Eight service members were lost that day leaving behind 17 children. A battlefield, and enduring promise, was immediately made by the remaining service members to provide full educations to the surviving children of those lost in the line of duty then, and in future generations – from that promise, Special Operations Warrior Foundation traces its roots.

Operation Eagle Claw helped transform United States military internal operating procedures. After investigations determined what occurred, the military developed the “joint doctrine.” As we mourn those who were lost, and though the situation is difficult to reflect on, there was good that came out of Operation Eagle Claw. It inspired a rebirth of Special Operations Forces within the United States military. The lessons learned from the mission resulted in the establishment of United States Operations Command, and subordinate commands designed to organize and employ joint Special Operations Forces worldwide.

Dedicated in 1983, the Iran Rescue Mission Memorial consists of a white marble column with a bronze plaque listing the names and ranks of those who lost their lives during the mission. Three of the men – Maj. Richard Bakke, Maj. Harold Lewis Jr. and Sgt. Joel Mayo – are buried in a grave marked by a common headstone, located about 25 feet from the group memorial.

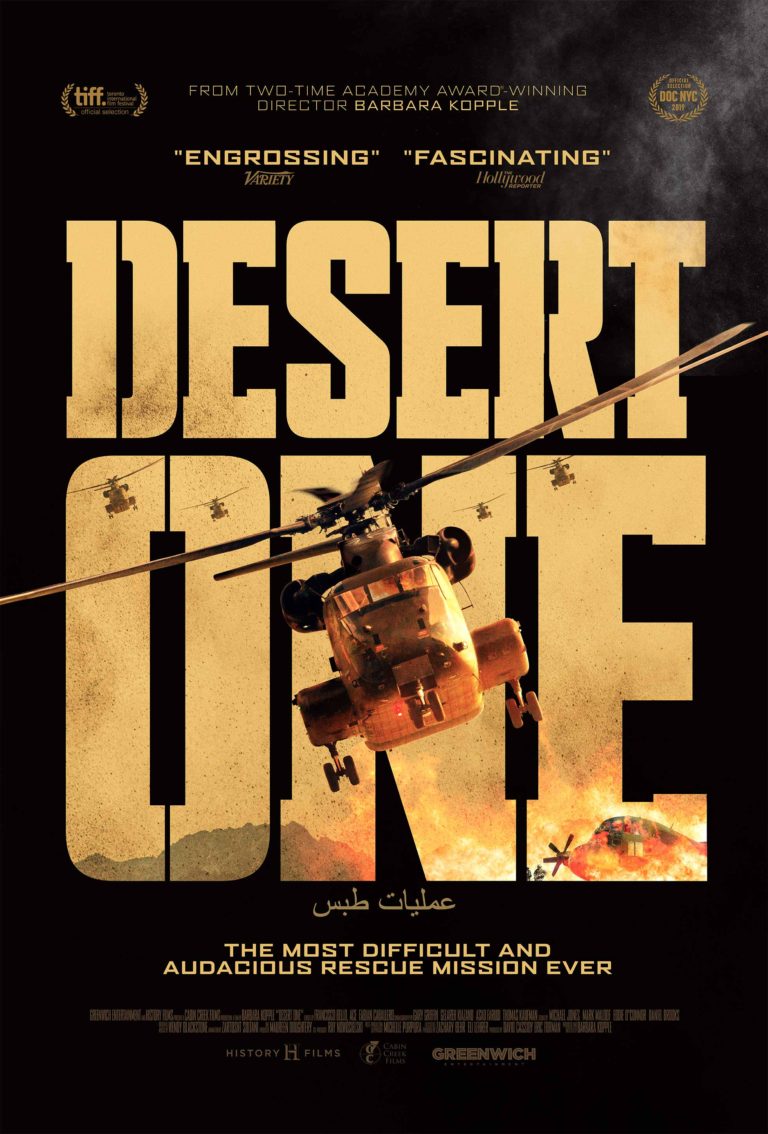

A powerful documentary depicting the events of Operation Eagle Claw and the tragedy at Desert One base in Iran was produced in 2019. You can find more information here.

From the documentary website: “Using new archival sources and unprecedented access, master documentarian Barbara Kopple reveals the story behind one of the most daring rescues in modern US history: a secret mission to free hostages of the 1979 Iranian revolution.”

A message from SOWF President

(1999-2013)

Colonel John T. Carney Jr,

USAF, Retired

John Carney was involved in Operation Eagle Claw and tells the story of how Special Operations Warrior Foundation initially started being proactive to find the surviving children of fallen special forces operators.

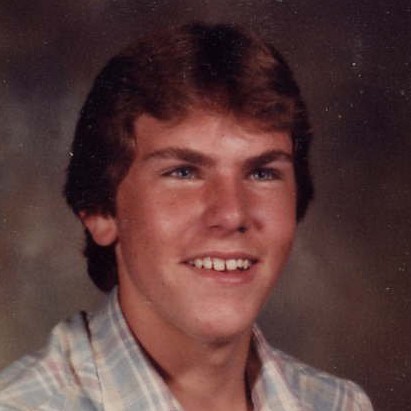

Graduate and son of Joel C. Mayo,

who was killed during Operation Eagle Claw in 1980 in Tehran, IranDoug first went to college in 1988 but ultimately decided to postpone his education to focus on his new wife and family. In 2014, Doug made the decision to return to school to get his degree in Nursing. Funded by SOWF, Doug graduated in 2017. He is now finishing his MS in Nursing and will soon be joining the many healthcare professionals on the frontline fighting the current health crisis.